Reflections on "Middlemarch: The Series," eight years later

Or, the wildest filmmaking challenge I've ever taken on

Once upon a time, in the year of our lord 2016, with the help of a fantastic group of actors, I embarked upon the most insane filmmaking adventure I’ve had to date — I wrote, directed, shot and edited Middlemarch: The Series, a 70-episode web series adaptation of George Eliot’s 1871 novel Middlemarch.

And eight years ago today, I was sitting in the sun room in my parents’ house wearing a Lowick sweatshirt I’d designed for the show, getting ready to hit “Publish” on the first episode.

The Form

When I started writing Middlemarch, the genre of the vlog-style literary web series was already pretty well-established.

The first official literary-inspired web series (or LIW) was the wildly popular Lizzie Bennet Diaries (2012), an adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice set in the modern day and shot as though it was a You Tube video blog (“vlog”), with the characters talking directly to the camera, “editing” the videos themselves, and even “releasing” the episodes themselves on their own YouTube channels.

After Lizzie Bennet came a spate of mostly lower-budget, often really great LIWs inspired by a whole range of classic works, including the much-admired Nothing Much To Do (2014), an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing created by a group of talented young people in New Zealand.

I think one thing that made the pseudo-vlog form work so well, for me and for a whole host of other young filmmakers, is that it’s a form that benefits from imperfections. Everything that could make a regular short film look “amateurish” or “unprofessional,” like shaky camerawork, imperfect lighting, not-professionally-styled hair and makeup, all actually added to the realism of the literary web series.

This I think is one reason why as the genre evolved, a lot of lower-budget LIWs were significantly more popular than their higher-budget counterparts. It was easy to imagine that these characters really were amateur YouTubers, filming themselves at home with an OK camera perched on a dubious tripod and a very bright lamp just out of frame, because often the reality wasn’t too far from the fiction.

The other huge advantage of the form was that it made something possible which would otherwise have been just about completely out of reach for low-budget young filmmakers: telling a long story over a long period of time.

To shoot a 5-minute dialogue scene between two seated characters in typical continuity style, you’d probably be looking at, at minimum:

1 two-shot where you can see both characters

1 medium close-up of character 1

1 medium close-up of character 2

1 closer close-up of character 1 for some emotional moment

1 closer close-up of character 2 for some emotional moment

1 or 2 inserts or establishing shots for the scene

Each of these shots requires finding a new framing for the camera, adjusting the lights as needed, moving any stray objects out of the background, and, for most of them, recording the entire scene — usually at least twice.

And that’s just for two characters who aren’t moving! If you throw in a third character or have them move around during the scene, which would require you to set up a new group of shots for the new location, you find yourself adding more and more shots.

Compare the time it would take to get all that done with the shots required to shoot a 5-minute conversation between two characters in a literary web series:

1 static tripod shot of the two characters

And that basically stays the same no matter how many characters you throw into the scene. Plus, video blogs rely heavily on jump cuts so there’s a lot of leeway for actors forgetting lines, because you can just shoot the scene in shorter chunks as needed and cut wherever you like.

This, for low-budget filmmakers, was basically revolutionary. Suddenly, young filmmakers, college students and even high schoolers who would have had a hard time getting together the funds, crew, and filmmaking know-how to make one “professional” short film were turning out whole 30- 40-, 70-episode web series, which were not only often quite good — but which lots of people actually watched and loved.

I found out about the Lizzie Bennet Diaries shortly after it finished airing, when I’d already been making films for a few years, and I knew as soon as I started watching it that I had to try my hand at making something like it. The only problem was that I didn’t know what to adapt. Enter Middlemarch.

The Adaptation

I first read Middlemarch for a class on the Victorian novel the spring of my sophomore year of college, and it more or less goes without saying that I fell utterly in love with it.

The titular town of Middlemarch is populated by a complex, at times comical, at times charming, at times appalling group of people whose lives intersect in a series of engrossing and unpredictable events. There are love stories, betrayals, deaths, births, crimes, local politics — really everything you could possibly want in a novel.

Even during my first reading of Middlemarch, I started fantasizing about what a modern adaptation of it could look like. And the summer before my junior year, over the course of a long drive from the San Francisco Bay Area to my part-time internship in Los Angeles, I mapped out a hypothetical literary web series adaptation of Middlemarch.

I started working on the series in earnest just about as soon as I got to Los Angeles, and I ended up spending more or less all my free time that summer outlining and then writing the show.

In working on the adaptation, I quickly discovered that one of my favorite things about the book was going to be the one thing that would be the hardest to adapt: the role of the narrator.

In the novel, it is Eliot’s omniscient narrator who interlaces the stories, at times making fun of the characters, at times zooming out from the story to draw parallels and make comically specific observations about human nature, and at all times preventing us from ruling out any one character as “just bad” or elevating one character as a “just good.”

The narrator is at the heart of the book — but a video blog series by definition doesn’t have a narrator, and it certainly can’t have an omniscient one.

I solved this seemingly unsolvable problem the same way I ended up addressing a number of adaptational challenges down the line: instead of focusing on the narrator in and of itself, I tried to figure out what the narrator’s presence was doing for the novel, and whether there was a way for me to also do that.

What I realized through this analysis is that I could substitute for a literal narrator the implied narration of editing. Instead of having the series take place “in real time” like the typical LIW, I framed the series as a project that Dot (my version of the book’s heroine, Dorothea) had been working on for the past six months and had now edited together. This meant that the episode titles could be quite significant and that a single episode could include separate, often intentionally interrelated clips from multiple characters.

For instance, at three different points in the novel, the narrator draws the reader’s attention to a human tendency to make plans for the future based on very shaky foundations — and the disastrous effects that can come from this “reckoning on uncertain events.”

In my adaptation, instead of simply giving this observation of the narrator’s to a single character, I rearranged the order of events to weave together those three moments into a single episode called Counting Chickens. The episode begins with one character worrying that he’s been bragging too much about having a prestigious internship “in the bag,” continues to another mapping out her entire romantic future with a man she’s just met, and ends with a third imagining for herself the whole future of a relationship that’s only just beginning.

This way, I left the interpretive work of drawing conclusions from these patterns to the viewer, but at the same time arranged and named the episode so that the viewer would be encouraged to draw those conclusions.

The basic principle I followed for the rest of the adaptation was to focus on the causes and effects of the various period events rather than hunting for exact modern equivalents — the goal at all times was to find a plausible modern event I could substitute for the period one while being able to keep the conversations before and after almost word-for-word identical to those in the book.

Looking back eight years later, there are certainly aspects of the adaptation that I would change if I were to go back and remake the series today, and I would love someday to take a stab at an actual period Middlemarch adaptation, but I think my general philosophy for adapting the book held fast, and the 360 or so pages I ended up with at the end of that summer felt — and still feel — to me like a vivid expression of the world of Eliot’s novel.

Once the series was written, though, I had to turn to the arguably much harder task of actually making the show.

The Production

One of the first challenges I faced trying to make the series was getting permission to do it as a year-long independent study, which would mean that I could take one fewer class each semester and have more time to work on the show. The problem was that the professor I’d been recommended to ask to be my advisor for it turned me down since, as he said, he just didn’t believe it was possible.

But it was! Luckily I did find a pair of excellent advisors, one for each semester, so I was able to lighten my course load after all, but that initial rejection stuck with me and was actually quite motivating when we hit the various inevitable roadblocks to getting the series done.

I cast first thing in the fall, and managed to assemble a phenomenal group of actors, mostly freshmen, and mostly from the school’s theater department.

I arranged the filming so that it took place every weekend, with one morning shoot (usually 9am - 12pm) and one afternoon shoot (usually 3pm-6pm) each weekend day, spacing out each character’s filming sessions so that most people only had at the most one or two shoots each weekend and only very rarely had two on the same day.

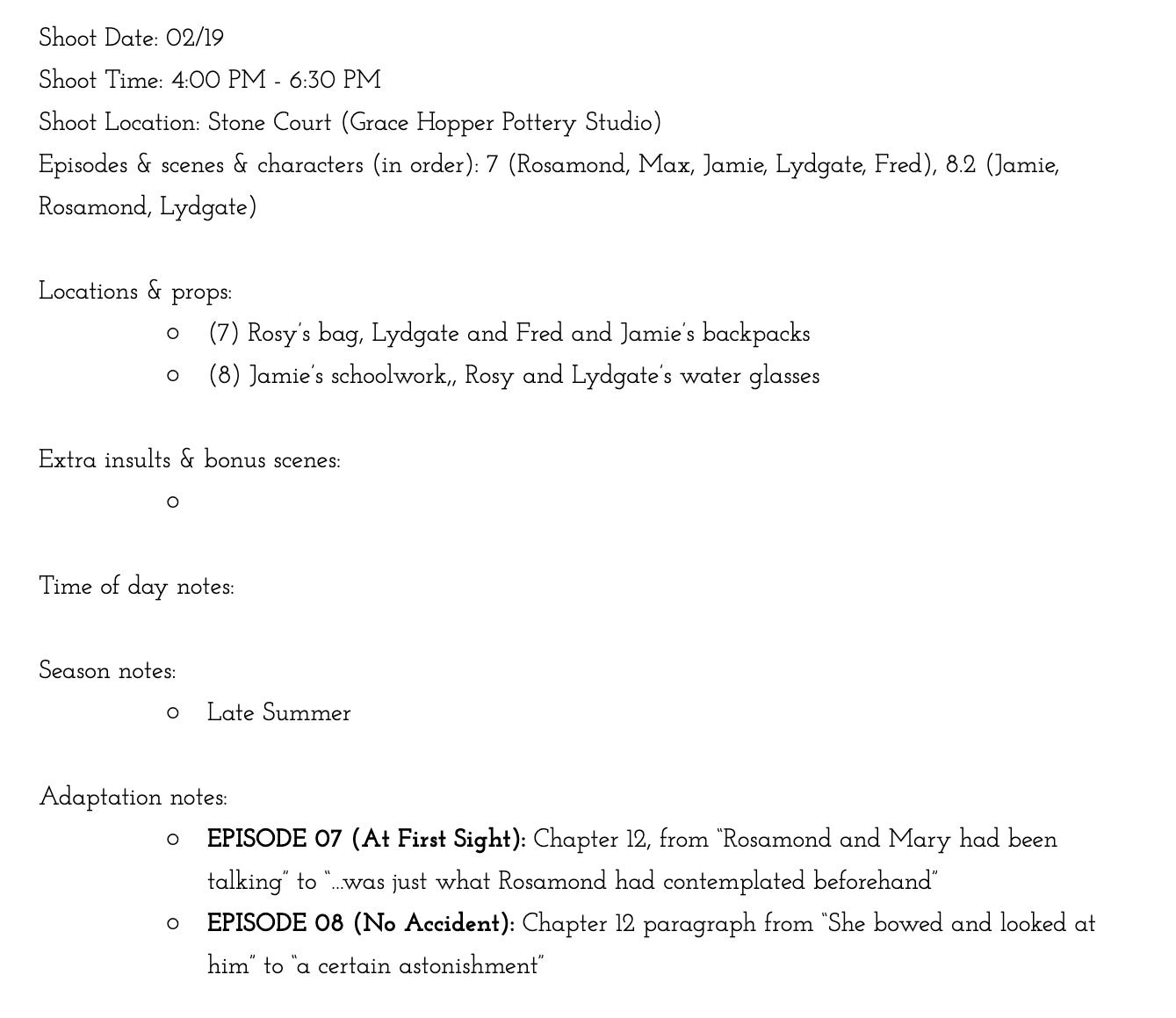

For each of these shoots, I’d assemble and send out a “Shoot Overview,” which listed the day, time, location, props, which episodes we’d be filming, and what part of the novel those episodes corresponded to.

Each shoot overview also had a section called “Character notes,” where I’d specify which scene the character was in, what costumes they needed and, most importantly, their “emotional context.”

I think more than anything, this emotional context was what made the project possible, and it’s an approach I return to for just about everything I make now.

Basically, over the course of working on the series, I created an insane 148-page single-spaced Google doc, where I wrote out each scene from each different character’s perspective. This included everything from their general emotional state going into the scene to what was behind specific hesitations or awkward pauses, to things they wanted to say but didn’t that were hovering under the surface and animating the conversation.

I then copy-pasted each character’s context into each episode so they could use it as they prepared the scene.

But why the hell did I do all that instead of just telling the actors what they needed to know when they showed up, or just letting them figure it out from the script?

Well, one of the things I like the most about Middlemarch as a novel that I tried to bring with me into the series is that every conversation is incredibly complicated — there’s a lot that goes unsaid, a lot of jokes that aren’t really jokes, a lot of moments of charged hesitation, basically a lot of emotional turbulence going on under the surface.

To get that all across, I knew I would need to do a whole lot of directing, but I also knew that for each of these shoots we’d have to film around 10-15 pages in each 3 hour block, so there wouldn’t be a lot of time for long conversations with the actors.

I also knew from my time in high school theater that it can be very helpful to have a clear sense of what the director imagines for your character while you’re learning the lines, so that you don’t memorize one approach and then have to change everything up when you arrive on set.

So while I did still find the time to do a lot of directing of the actors to get the emotional moments to come across exactly right, it was this shared understanding of the characters’ emotional state for each scene — along with the fantastic prep work the actors were doing behind the scenes — that really made that fine-tuning possible, and meant that we could uncompromisingly shoot something so rich and emotionally complex in such a short time.

And now even when I have much more time on set, I still usually write up and send out emotional context before the shoot — and there’s a running joke with my actors that the context is usually significantly longer than the script. But what can I say? Even putting aside the benefits of sending out the emotional context to the actors, just taking the time to think through each scene from each person’s point of view alone is an invaluable exercise for a director, and one I never want to skip.

The production of Middlemarch, like any film production, was riddled with the inevitable setbacks — schedules changed, actors dropped out, whole episodes had to be re-shot, moments that seemed like they were going to be great had to be removed and replaced in the editing room, etc. etc.

But we did it! On May 2nd, 2017, we wrapped the last episode of the series, and that whole spring, summer and fall was a whirlwind of bi-weekly episode releases, thrilling and unexpected press coverage, and the growth and development of a lively fan community — all of it much more than anything I could have imagined when I started writing the year before.

I haven’t yet made anything else as crazy as Middlemarch, or anything that has had the same fanbase or press coverage swirl up around it, but the experience of making that show happen underlies everything I make today — I’m still writing up emotional context, sending out shoot overviews, adapting works of classic literature, and leading actors through complex, multilayered dialogue scenes.

The world has changed a lot since we made Middlemarch, and the era of the literary web series seems quite some time ago now. There are certainly aspects of that time that I don’t miss, like the constant fear of being labeled “problematic” for any misstep or the many many hours I wasted on Tumblr and Twitter, but I still look back fondly at those days when young filmmakers with tiny budgets were making shockingly compelling, long-form series just about everywhere you looked.

I have no idea what the future of ~media~ or ~web series~ or ~the internet~ holds, but I’m very encouraged by the move away from ad-ridden, empty social media towards local community and longer-form DIY writing and art, and I’m excited to see what new kinds of zero-budget art come out of this new world — and what kinds of insane, seemingly impossible projects I and my generation of filmmakers take on next.

But for now, here’s Middlemarch:

If you’d like to hear more of my scattered, hopefully-not-always-this-long musings on filmmaking, you’re more than welcome to subscribe to this newsletter, and if you’d like to see what I’m working on now, feel free to subscribe to The Film Club, a private, slightly more personal newsletter, where I send out my new films and web series episodes early, accompanied by longer-form commentary about how each one came to be.

Thanks for stopping by — and until next time,

Rebecca

oh how time flies!! and what a wonderful glimpse into your process

Middlemarch the Series was fantastic and i think about it lots - my name comes from Jamie Chettam for example! very much appreciate all the work you put in to making it happen :))